“The Isaiah Scroll, the most important of the Qumran scrolls and the very ‘body’ of the Bible, presented to the Community.”

- Giovanni Panzeri

- May 23, 2023

- 3 min read

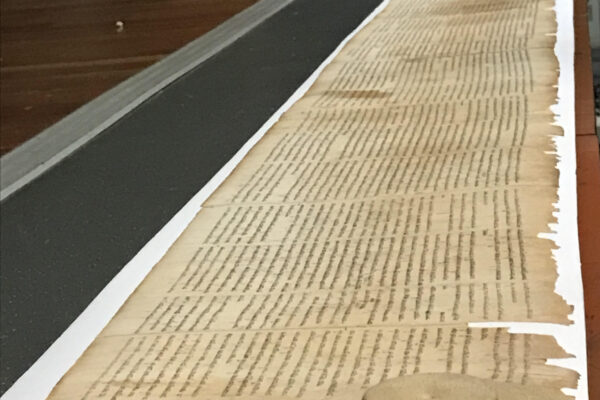

“I consider these manuscripts, particularly the Isaiah Scroll, to be the body of the Bible. In the past, scholars regarded the Bible as an abstract entity to be reconstructed. Today, thanks to these scrolls, we have tangible artifacts.”

These were the words of Marcello Fidanzio, head of the Qumran excavations for the Israel Museum in Jerusalem, spoken during the second part of the evening event organized on Wednesday, May 24, by the Jewish Community of Milan in the Aula Magna of the Jewish School. The conference had a dual purpose: to present the community’s new online portal and to display one of the ten copies of the Isaiah Scroll, perhaps the most famous of the Dead Sea Scrolls—a collection of ancient Jewish religious manuscripts dating from between 200 BCE and 70 CE, discovered between 1947 and 1956 in cave systems near the ancient settlement of Qumran in the West Bank.

The event opened with a brief address by Davide Blei, Head of Communications for the Jewish Community of Milan and President of the Association of Italian Friends of the Israel Museum (AIMIG), who emphasized the importance of the scrolls for international Judaism.

“The Isaiah Scroll was written in Hebrew 200 years before the birth of Christ,” Blei explains, “and a second-grade child in Tel Aviv can read the language in which it was written. This artifact shows that over these millennia the Hebrew language has not changed; texts more than two thousand years old can still be read today. And it is not important only for Jews: from our monotheism both Christianity and Islam developed. The Isaiah Scroll,” he concluded, “could be described as the Scroll of the World.”

The floor then passed to Fidanzio, who described the troubled history of the discovery, recovery, and study of the Scrolls, highlighting, among other things, the symbolic importance of the recovery of the first three manuscripts by archaeologist Eleazar Sukenik on November 29, 1947—the very day on which the United Nations recognized the State of Israel by voting in favor of the partition plan for Palestine.

“There are 950 religious manuscripts written in Hebrew, Aramaic, and Greek,” Fidanzio explained. “Twenty-five percent are biblical texts; another 25 percent concern the particular Jewish group that produced and preserved the manuscripts (identified by some scholars as the Essenes), an elite community that stood in opposition to, yet was also in contact with, other Jewish communities of the time. In fact, more than half of the manuscripts are examples of religious literature common to late Second Temple Judaism—much of which was previously unknown to us.

“The Isaiah Scroll alone accounts for 20 percent of all the biblical texts found at Qumran,” Fidanzio continued, “and on it we find the marks of everyone who handled it—those who preserved it, corrected it, corrected it again, and studied it. It is an object that will continue to tell us more and more about what the Bible meant to those who created and used it. It has a vitality that goes beyond its mere content.”

Today, according to Fidanzio, the goal of the work at Qumran is no longer so much to decipher the content of the Scrolls—which is now well known—or to discover new ones, but rather to understand the historical framework of Judaism at the time, and in particular that of the community that wrote and cared for them.

“The content of the Scrolls ends around 50 BCE, but the writing of the latest ones dates to a century later,” Fidanzio concluded. “The Scrolls do not tell us their own story—why they ended up in the caves, who assembled them, and when. These are questions that must be addressed by the material context: archaeology.”

Comments